Artificial intelligence (AI) systems and in particular generative AI (GenAI) systems have raised the question as to whether technical advances in the useful arts or synthetic content generated using these tools can qualify for patent or copyright protection. Recent decisions in both the patent and copyright fields have rejected protection for otherwise patentable inventions and copyright works when identifying the sole claimed inventor or author as an artificial intelligence system. The recent UK Supreme Court decisions in Thaler (Appellant) v Comptroller-General of Patents, Designs, and Trade Marks [2023]UKSC 49 and the US Copyright Review Board in Refusal to Register SURYAST are illustrative.

Do generative AI inventions qualify for patent protection

Prior to the UK Supreme Court decision in Thaler, courts that have considered the question have largely held that an inventor of otherwise patentable subject matter must be a natural person. This was the decision reached in the United States by the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals in Thaler v Vidal 43 F.4th 1207 (2022) which ruled that Section 271 of the Patent Act requires that an inventor be a human being. The European Patent Office reached the same conclusion in J 0008/20 (Designation of inventor/DABUS) of 21.12.2021 as did Australia’s Full Court in Commissioner of Patents v Thaler ‑ [2022] FCAFC 62.

UK Court of Appeal in Thaler v Comptroller General of Patents

The UK Court of Appeal in Thaler v Comptroller General of Patents, Trade Marks, and Designs [2021] EWCA Civ 1374 (21 September 2021), the decision appealed to the UK Supreme Court, also declared that a human being must be the inventor.

Unsurprisingly, the UKSC concluded that, as a matter of statutory construction, the meaning of “inventor” under the UK Patents Act 1977 had to be a natural person.

I must state immediately that every level in these proceedings and every judge who has considered it has decided against Dr. Thaler on this issue. Throughout, Dr. Thaler has argued that DABUS, not himself, devised the technical advances and the new products described and disclosed in the applications, and that DABUS was their inventor. As I have indicated, the Comptroller accepts for the purposes of these proceedings the substance of the factual case advanced by Dr Thaler, namely that DABUS created or generated the technical advances described and disclosed in the applications and did so autonomously using AI, but the Comptroller has never accepted (and disputes any suggestion) that this renders DABUS an inventor within the meaning of the 1977 Act.

sections 7 and 13 of the Act

In my judgment, the position taken by the Comptroller on this issue is entirely correct. The structure and content of sections 7 and 13 of the Act, on their own and in the context of the Act as a whole, permit only one interpretation: an inventor within the meaning of the 1977 Act must be a natural person, and DABUS is not a person at all, let alone a natural person: it is a machine and on the factual assumption underpinning these proceedings, created or generated the technical advances disclosed in the applications on its own. Here I use the term “technical advance” rather than “invention”, and the terms “create” or “generate” rather than “devise” or “invent” deliberately to avoid prejudging the first issue we have to decide. But it is indisputable that DABUS is a machine, not a person (whether natural or legal), and I do not understand Dr Thaler to suggest otherwise…

In all these circumstances the Comptroller was right to decide that DABUS is not and was not an inventor of any new product or process described in the patent applications. It is not a person, let alone a natural person and it did not devise any relevant invention. Accordingly, it is not and never was an “inventor” for the purposes of section 7 or 13 of the 1977 Act.

Dr Thaler had also argued that he was nevertheless the owner of the “invention” under the “doctrine of accession”. This argument had been rejected by Arnold JA in the Court of Appeal and it was also rejected by the UKSC.[i]

Commentary re computer generated patentable inventions

In Thaler, the UKSC made it clear that its decision was not dealing with the larger policy question of whether, or in what circumstances, an AI generated non-obvious technical advance should be patentable. Moreover, the decision’s grounds were confined to the more specific issue of accurately interpreting and applying the pertinent provisions of the 1977 Act to Dr. Thaler’s applications.

The Comptroller has emphasised, correctly in my view, that this appeal is not concerned with the broader question whether technical advances generated by machines acting autonomously and powered by AI should be patentable.

Additionally, it neglects to address the exploration of whether the term “inventor” ought to be expanded to encompass AI-powered machines that create new and innovative products and processes, potentially surpassing known counterparts in benefits.

These questions raise policy issues about the purpose of a patent system, the need to incentivise technical innovation and the provision of an appropriate monopoly in return for the making available to the public of new and non-obvious technical advances, and an explanation of how to put them into practice across the range of the monopoly sought. It may be thought that the rapid advances in AI technology in recent times render these questions even more important than they were when these applications were made.

UKSC

The UKSC also pointed out that the decision did not address the very practical, important, and different question of whether, or in what circumstances, a natural person could obtain a patent when making a technical advance using a generative AI system.

It follows but is important to reiterate nonetheless that, in this jurisdiction, it is not and has never been Dr Thaler’s case that he was the inventor and used DABUS as a highly sophisticated tool. Had he done so, the outcome of these proceedings might well have been different.

Similar questions were raised by the Full Court of Australia in Commissioner of Patents v Thaler.

In our view, there are many propositions that arise for consideration in the context of artificial intelligence and inventions.In considering whether to redefine a person as an inventor to include artificial intelligence, one must address key policy questions. If recognition occurs, the patent’s grantee could be the machine owner, software developer, copyright holder of the source code, data input provider, or others. The recalibration of the inventive step standard is crucial, and if so, the criteria should no longer align with the knowledge of an uninventive skilled worker. The approach for recalibration needs careful consideration. What continuing role might the ground of revocation for false suggestion or misrepresentation have, in circumstances where the inventor is a machine?

Those questions and many more require consideration. Having regard to the agreed facts in the present case, it would appear that this should be attended to with some urgency…

characterization

However, the characterisation of a person as an inventor is a question of law. This litigation has not explored whether the application subject to this appeal has a human inventor, and the matter remains undecided. If examined, it might have been necessary to consider the significance of various factors, including the agreed facts that Dr. Thaler owns the copyright in the DABUS source code, the computer operating DABUS, and is responsible for maintenance and running costs

They did not consider if the unauthorized handling of the product could violate that right under a tort conversion theory or if any such right would be preempted by an IP

Do generative AI works qualify for copyright protection

Copyright law has long held that an author must create an original work. While using a computer-based tool is acceptable, the person must contribute enough independent intellectual effort to qualify as the author The distinction between computer-assisted and computer-generated works is based on this principle.[ii]

The US Copyright Office has issued several decisions denying copyright recognition for computer-generated works but permitting copyrights with disclaimed AI-generated portions. A District Court, in the Thaler v Perlmutter case, followed the Copyright Office’s position.

The US Copyright Office Review Board confirmed the position of the US Copyright Office in a recent case refusing to register the 2 dimensional artwork called SURYAST produced by Mr Sahni.

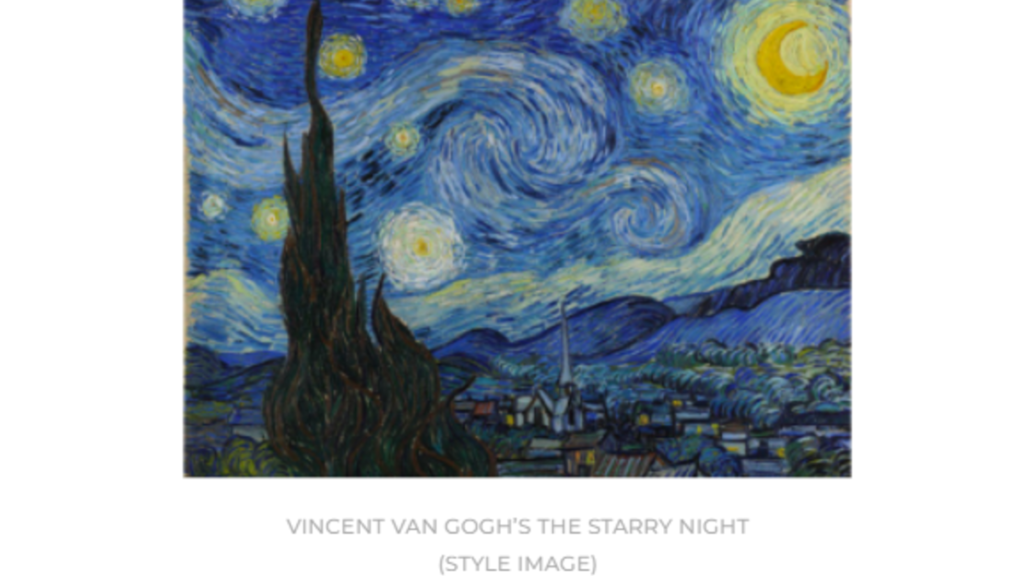

RAGHAV, a generative AI tool, produced the two-dimensional artwork by using a base image (Mr. Sahni’s original photograph), a style image (Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night), and an undisclosed numerical value for the strength of the style transfer RAGHAV then generated SURYAST work using the GenAI system RAGHAV.

Moreover, the original photograph serving as the base work, the van Gogh style image, and the submitted work for registration are displayed below.

Readmore : Pakistani Health-Tech Startup, Led by Women, Secures $2.7m in Funding

Leave feedback about this